Posted: September 3rd, 2025

How to Write a Case Study: A Complete Guide for Students (With Examples)-2025

Introduction: Why Case Studies Matter

A case study is far more than a neat story wrapped around a problem. At its best, it is a disciplined, evidence-based exploration of a real situation that asks you to connect theory to practice, sift competing explanations, and recommend defensible actions. That’s why case studies appear everywhere in academia—business schools use them to simulate boardroom decisions; law faculties use them to trace how precedent shapes outcomes; medical programs use them to train clinical reasoning; psychology courses use them to examine behavior in context; and education programs use them to evaluate classroom interventions. For students, learning to write a case study is not simply a way to collect marks. It is training in how to think: how to frame a problem precisely, choose and apply appropriate analytical tools, weigh incomplete or conflicting data, and articulate clear, actionable conclusions.

In an era saturated with information, the case study also teaches restraint and relevance. You cannot include everything you’ve read; you must decide what actually moves the analysis forward. That means distinguishing between background that sets the scene and evidence that changes the diagnosis or the recommended solution.

It means translating abstract concepts—competitive advantage, informed consent, cognitive bias, formative assessment—into concrete criteria you can test inside the case. It also means writing for a specific audience, whether that is an instructor evaluating your mastery of a framework, a practitioner seeking insight, or a peer reviewer looking for methodological rigor. When you develop these habits, you build the very skills employers prize: critical thinking, problem-solving, data literacy, ethical judgment, and persuasive communication.

Case studies matter for another reason: they model uncertainty. Unlike textbook problems, cases seldom present clean variables or tidy endings. Data may be partial, stakeholders may disagree, and constraints—budget, time, regulation—may rule out theoretically elegant solutions. Working inside these limits forces you to articulate assumptions, acknowledge trade-offs, and justify why one course of action is better than the alternatives given the evidence at hand. This is precisely how decisions are made outside the classroom, which makes case writing an authentic rehearsal for professional practice.

Finally, strong case studies are inherently persuasive. They don’t just report what happened; they make a case—hence the name. Through careful structure, judicious use of evidence, and logically sequenced reasoning, they lead readers from problem recognition to conclusion. When your analysis is clear and your recommendations are feasible, your reader should feel that your conclusion was not only possible but inevitable.

What Is a Case Study?

At its core, a case study is a focused, systematic analysis of a single subject—a company, a patient, a policy decision, a classroom, a community program, even a single event—examined within its real-world context. Writing one typically involves four interlocking tasks: describing the context with enough detail for the reader to understand the stakes; identifying and framing the central problem or research question; analyzing the case using appropriate theories, models, or methods; and proposing solutions or drawing conclusions supported by evidence.

What distinguishes a case study from a general essay or a broad research paper is its specificity and its commitment to context. Rather than surveying an entire field, you zoom in on a particular instance and ask, “What is going on here, and why?” That focus allows you to test theory against reality. A business student, for example, might examine Apple’s marketing strategy in a specific product launch, using frameworks like STP (segmentation, targeting, positioning) or the 4Ps to explain how choices about pricing and messaging shaped consumer adoption.

A medical student might document the treatment of a patient with a rare condition, detailing presenting symptoms, differential diagnoses considered and ruled out, investigations ordered, therapeutic decisions made, and the ethical considerations that guided consent and follow-up. A law student might evaluate a landmark judgment, tracing how facts, statutes, and prior precedent interacted to produce the ruling and what implications follow for future cases.

Methodologically, case studies can be qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods. You might analyze interview transcripts, field notes, and documents; you might work with financial statements, survey data, or experimental measures; and often you will triangulate several sources to strengthen validity. The key is transparency: explain how you gathered and interpreted the evidence so that readers can assess the credibility of your claims. Ethical considerations also matter. When individuals are involved, you should protect privacy, secure consent where required, and avoid harm in reporting.

Good case studies are selective but sufficient. They include the facts that change the analysis—timelines, constraints, stakeholder incentives, performance indicators—while omitting noise that adds length without insight. They use theory as a lens rather than a shield: models illuminate patterns and causal mechanisms, but they do not substitute for evidence. And they culminate in warranted judgments: clear findings, practical recommendations, or lessons learned that someone else could apply in a similar context.

In short, a case study is a bridge between classroom knowledge and the messy world of practice. By narrowing the frame to a single, well-chosen instance and then examining it rigorously, you learn how to diagnose problems, justify decisions, and communicate solutions—skills that travel with you well beyond the assignment.

Types of Case Studies

Case studies are not all alike; they vary significantly depending on the academic discipline, the purpose of the investigation, and the kind of questions the researcher is trying to answer. Understanding these differences is essential because the type of case study you choose will directly influence your approach, the structure of your writing, the kind of data you collect, and even the tone of your analysis. Broadly speaking, case studies can be grouped into explanatory, exploratory, descriptive, intrinsic, and instrumental types, though there are also combinations and subcategories that may appear in more advanced research.

Explanatory case studies are designed to explore cause-and-effect relationships. They are particularly valuable when a researcher wants to understand not only what happened but also why it happened. For instance, a public health researcher might conduct an explanatory case study on how a vaccination campaign in a rural community succeeded in reducing disease rates. Instead of simply describing the campaign, the study would analyze the relationship between factors such as community engagement, government support, and health education, showing how each contributed to the observed outcomes. Explanatory case studies are therefore more analytical in nature, making them a popular choice in fields like political science, sociology, and epidemiology where understanding causality is central.

Exploratory case studies, on the other hand, are more open-ended. They are usually conducted at the early stages of research when the researcher is still trying to identify key variables, possible questions, or methods that could guide a larger investigation. These studies are like pilot projects that pave the way for more systematic research later. For example, a business student might conduct an exploratory case study on how startups in a particular city are responding to new tax laws. The goal would not be to arrive at definitive conclusions but rather to identify trends, issues, and potential areas for deeper analysis. Exploratory case studies are particularly useful in fast-changing fields like technology, business, or education, where conditions evolve rapidly and researchers need to first map the terrain.

Descriptive case studies focus on providing a detailed, factual account of a situation or event. Unlike explanatory studies, they do not primarily seek to analyze causality. Instead, they present a comprehensive narrative that helps the reader understand what happened in a particular case. For example, a historian might write a descriptive case study about the development of a specific neighborhood over time, focusing on population changes, architectural styles, and cultural influences. In medical studies, a descriptive case study might document a patient’s rare symptoms and progression of disease to provide future practitioners with a reference point. These studies are often rich in detail and valuable for building a repository of knowledge that others can draw from.

Intrinsic case studies are driven by curiosity about a unique or unusual case rather than by the need to generalize findings. The purpose is not necessarily to solve a broader problem but to learn as much as possible about a particular case that is special in its own right. For instance, a psychologist might conduct an intrinsic case study of a patient with a very rare psychological disorder to better understand the individual experience. Similarly, a literary scholar might examine a single novel in detail, not because it represents an entire genre, but because it holds particular significance for them or the field. These studies emphasize depth over breadth and allow the researcher to deeply immerse themselves in the subject.

Instrumental case studies, by contrast, use a specific case as a lens to understand something larger. The individual case is important, but primarily because it illustrates or sheds light on a broader issue. For example, a researcher might study one school’s approach to digital learning in order to draw conclusions about the challenges and opportunities of technology in education more generally. The school itself is not the ultimate focus; rather, it is a vehicle for understanding wider educational practices and policies. Instrumental case studies are common in social sciences and education, where researchers often use examples to highlight systemic trends.

Choosing the correct type of case study is more than an academic formality; it shapes everything from the design of your research to the way you write up your findings. An explanatory case study demands rigorous analysis of causes and effects, often supported by data and theory. An exploratory one invites flexibility and openness, emphasizing observation and the identification of new questions. Descriptive case studies require strong narrative skills and attention to detail, while intrinsic studies benefit from empathy and depth of focus. Instrumental case studies call for balance—analyzing the individual case carefully while also connecting it to larger patterns or theories.

In short, knowing which type of case study you are writing is the first step in producing a high-quality paper. It helps set your expectations, guides your research design, and signals to your reader what kind of insights they can anticipate. Whether your goal is to explain a phenomenon, explore a new issue, describe a unique situation, dive deeply into a special case, or use a single example to illuminate a broader theme, selecting the right type of case study ensures that your analysis is coherent, focused, and meaningful.

Step-by-Step Guide to Writing a Case Study

The process of writing a case study can feel overwhelming, but breaking it down into steps makes it much easier. The first step is to understand the assignment. Carefully read your professor’s instructions and pay attention to word count requirements, formatting style (such as APA, MLA, or Chicago), and the expected level of research.

The second step is to select and define the case. Choose a subject relevant to your field of study and clearly define the boundaries of your research. For example, if you are analyzing Tesla’s business model, decide whether you will focus on marketing, production, or innovation. Defining the scope early helps you stay focused throughout the writing process.

The third step is to conduct thorough research. Use credible academic sources such as peer-reviewed journals, books, industry reports, and even interviews or surveys where appropriate. The goal is to gather enough information to understand the context and support your analysis.

Once you have collected the necessary data, the fourth step is to organize your information. Categorize your notes into themes such as background information, problem identification, data analysis, and recommendations. This will give your case study a logical structure.

The fifth step is drafting the case study. Begin with a strong introduction that sets the stage, move into background details, state the problem clearly, analyze the data, and then present solutions or recommendations. Write in a formal academic tone and back up your points with evidence.

Finally, the sixth step is to revise and edit your work. Carefully proofread for grammar errors, structural issues, and clarity. Ensure that your references and citations follow the required academic style.

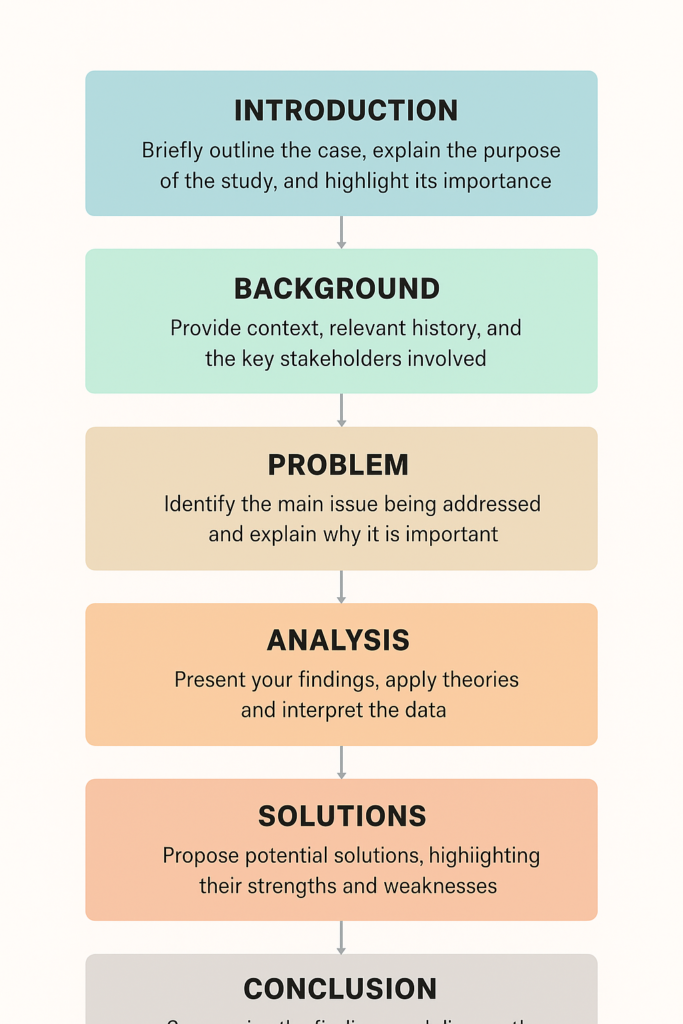

Structure of a Case Study

A well-written case study generally follows a structured format that ensures clarity and logical flow. The first component is the introduction, which sets the stage by briefly outlining the case, explaining the purpose of the study, and highlighting why it matters. A strong introduction grabs the reader’s attention while establishing the relevance of the case within its academic or professional context.

The next section is the background information. This part provides the necessary context by describing the history, environment, and circumstances surrounding the case. It also introduces the key stakeholders or individuals involved. The goal here is to give the reader enough information to understand the situation without overwhelming them with unnecessary details.

Following the background comes the problem statement. This is a critical element because it identifies the central issue or challenge that the case study seeks to address. A clear and concise problem statement explains what the issue is, why it is important, and what is at stake if it is not resolved.

The analysis section is the heart of the case study. Here, you present your findings, apply relevant theories, and interpret the data you have collected. This part often involves comparing different perspectives, evaluating evidence, and identifying patterns or causal relationships.

Once the analysis is complete, the next step is to present proposed solutions. This section outlines potential ways to address the problem and evaluates the strengths and weaknesses of each option. Solutions should be realistic, evidence-based, and supported by reasoning.

Finally, the conclusion wraps up the case study by summarizing the key findings and emphasizing their significance. It may also suggest implications for future practice, research, or policy, leaving the reader with a clear understanding of what was learned and why it matters.

Examples of Case Studies

Examples can make the concept of case studies clearer. In business, for instance, a case study on Starbucks’ global expansion strategy may begin with background details on how the company faced challenges entering emerging markets. The problem identified would be cultural differences and high competition. Analysis might include examining the company’s menu adaptation and localized supply chain. The solution would focus on how Starbucks customized its strategies per region, leading to improved growth. The conclusion would highlight that cultural adaptation is essential for global business success.

In law, a well-known case study is Brown v. Board of Education (1954). The background would describe the racial segregation policies in U.S. schools. The problem would focus on whether segregation violated constitutional rights. The analysis would review constitutional arguments, prior rulings, and social impact. The solution was the Supreme Court’s decision that segregation was unconstitutional, and the conclusion demonstrated how the case set a legal precedent for civil rights.

In psychology, one famous example is Phineas Gage’s brain injury. The background describes how Gage, a railroad worker, survived a traumatic brain injury in 1848. The problem explores the effects of frontal lobe damage on behavior and personality. The analysis relies on observations of his dramatic behavioral changes after the accident. The conclusion emphasizes how his case provided groundbreaking insights into the relationship between brain function and personality.

Common Mistakes in Case Study Writing

Many students make the same mistakes when writing case studies. One of the most common errors is a lack of focus, where the writer tries to cover too much instead of sticking to a single case or issue. Another mistake is insufficient research, relying only on surface-level information without consulting academic sources. Some students fall into the trap of being too descriptive rather than analytical, merely summarizing the case without interpreting its meaning or significance. Poor structure is another common problem; disorganized writing confuses the reader and undermines the credibility of the work. Lastly, failing to properly cite sources can lead to plagiarism issues, which carry serious academic consequences.

Tips to Make Your Case Study Stand Out

If you want your case study to stand out, you must go beyond the basics. Use real data and evidence whenever possible to make your analysis more persuasive. Apply relevant theories and frameworks from your discipline to give your work academic depth. Write in a clear, concise, and professional tone, avoiding unnecessary jargon. Visuals such as charts, graphs, or tables can also make your case study more engaging and easier to understand. Finally, focus on the practical implications of your findings—professors and readers appreciate work that not only analyzes but also suggests meaningful solutions.

Conclusion

Writing a case study requires more than summarizing a situation; it is about analyzing, interpreting, and proposing solutions to real problems. By following the steps and structure outlined in this guide, students can craft compelling case studies that demonstrate their research skills, critical thinking, and ability to apply theory to practice. The key is to remain clear, focused, and evidence-based. With practice, case study writing can become one of the most rewarding and valuable parts of your academic journey.

Expert paper writers are just a few clicks away

Place an order in 3 easy steps. Takes less than 5 mins.